Inheritance

In a world that is continually diversifying and becoming more blended, I’ve seen many people who experience difficulty navigating between the language and culture they gain from their heritage with that of their place of upbringing, myself included. My family is a blend of Chinese and Vietnamese cultures. Being a first–generation American, I’ve often had a difficult time expressing myself in languages other than English while also feeling like an outsider on all fronts. Each member of my family (extended and immediate) has varying degrees of experience in each language, and communication has always been difficult. By combining language with the experiential and the immaterial, my project seeks to evoke both the challenges and the rewards of growing up bilingual in a multicultural America—that while understanding is often difficult, with time and effort language can fall into place and communication can become clear.

Growing up I always felt very American; all my friends spoke English, my cousins and I would play games and interact in English. Hints of Vietnamese and Chinese culture came up in my everyday life but for me this felt normal. We would eat leftover dim sum for breakfast and on weekends we would spend the days at my grandmother’s house only hearing Chinese from the adults. Holidays were spent attending Vietnamese mass and special occasions took place in the party room of the Chinese restaurant where my dad worked. My parents would talk to me in one language and I would answer in another seamlessly. When I was young I didn’t even know there was a difference between these languages because when I spoke, no matter what languages I used, I was always understood. As I grew I began to lose this ability; I spoke in English to everyone and we would all get by. I became more and more American without a second thought but now as I get older, there is a longing for cultures I’ve never quite fit in. I often feel absent with my extended family because of the lack of understanding I have and the inability to communicate without someone translating.

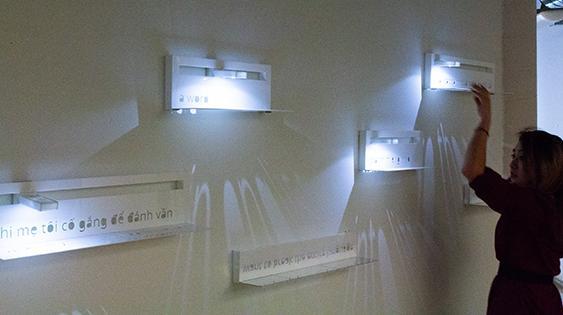

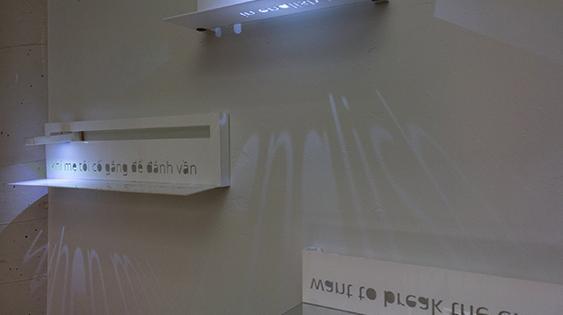

My project—an installation—is a series of shelves that incorporate a narrative. Upon first glance the installation is difficult to understand unless you can read in Vietnamese and in English, a skill that even I don’t possess. The narrative—a short poem—is in a sense hidden in this work. The lights act as a tool for reading translations from the presented Vietnamese into illuminated, distorted English. Even with the provided tools, the English isn’t perfectly legible and still takes time to understand and read. Then, when you think you know how to read the poem, mirrors come into play; the multiple methodologies needed to understand the writing express that there are multiple ways to understand a language, a culture, or another person.

I’m hopeful this project will be meaningful to those that regularly confront multiple languages and cultures, and that it translates the process necessary to express oneself to others who may not speak the same native language. I also hope that it communicates what understanding feels like—both the challenges and the rewards—to those who don’t often have this struggle. The interactive commonent of this project is critical to me. Communication between multiple cultures and languages is very hands on and at times very intimate. This is a process that is unique to each and every individual, because everyone’s experiences and levels of understanding with multiple languages is different.

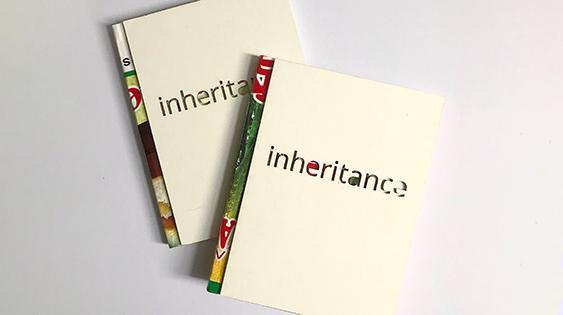

Aspects of this are taken into my book as well. Cutout pages and decoder pages create a mix of methodologies that require personal, intimate interaction with the book to understand or see the messages. My writings in the book are very personal—I wanted everything to sound authentic and approachable. I’ve also included excerpts from other people, written in their own voices, to portray this feeling of personal experience and identity with multiple cultures and languages.